You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Aircraft’ category.

For the month of April, I decided to do something a little different. I left it to my readers to ask the questions to discover more about something that they did not know. I was happy to see a few inquiries come back. The last week of this month will focus on the answers to your questions. Thank you to all who participated and for those who did not get their request in, please email me at loveofflight@thepublichistorian.net or post a message on this webpage and I will get started on the research for you.

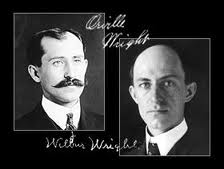

One of the first inquiries I received was in regards to the Whitehead-Wright controversy of who was really first in flight. This debate has been sparked every so often in the media questioning who should take the fame for achieving man’s ability to fly heavier-than-air machinery. Let’s first introduce the characters in our historical narrative. Many of us aviation buffs are familiar with the Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur, who flew their flyer above the outer banks of North Carolina in 1903. Known as the individuals to be “first in flight” they laid the foundation for the aviation industry.

One of the first inquiries I received was in regards to the Whitehead-Wright controversy of who was really first in flight. This debate has been sparked every so often in the media questioning who should take the fame for achieving man’s ability to fly heavier-than-air machinery. Let’s first introduce the characters in our historical narrative. Many of us aviation buffs are familiar with the Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur, who flew their flyer above the outer banks of North Carolina in 1903. Known as the individuals to be “first in flight” they laid the foundation for the aviation industry.

Little did anyone know that there was another inventor that claimed that title a few years prior. Gustave Whitehead, an immigrant from Bavaria, Germany who was born on January 1, 1874. Whitehead had always been fascinated with flight. Schoolmates dubbed him “The Flyer” due to his intense study of birds and building model parachutes and gliders. He pursued his passion for aviation and in 1895 decided to immigrate to America to continue his research.

According to the historians of gustavewhitehead.org, the “story of Gustave would not be known today if it wasn’t for dedicated researchers from 1937 on who have been tracking down evidence to substantiate the Whitehead first flight claim. In particular, journalist Stella Randolph who wrote ‘The Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead’ (1935 publication of Popular Aviation) and ‘Before the Wright flew: The story of Gustave Whitehead’” (1937). According to Randolph and her co-writer, Harvey Phillips, Whitehead successfully flew three different powered aircraft. His first flight conducted in 1899, Whitehead flew in a steam-driven aircraft. Then in August of 1901, he made another flight with a gas-powered aircraft, designated “Number 21” and with “Number 22” the following year. If true, these flights would prove that Whitehead preceded the Wright brothers in powered flight. (to see article, click here)

Several of Randolf and Phillips’ assertions in the article are a bit peculiar and have drawn critics to question the validity of their evidence. Let’s put to the side that it was more than three decades after the flights and nine years after Whitehead’s death in which the article was written, which could possibly taint any evidence that existed, i.e. people’s memory of the event and that no follow up could be made with Whitehead. Much of the article drew from a previous story by The Bridgeport Herald newspaper published on August 18, 1901. The journalist claimed he witnessed a night test of the plane in which at first it was unpiloted but filled with sand bags with a second follow-up flight with Whitehead at the controls. To begin, an initial testing of an aircraft’s flight ability at night is extremely dangerous even by today’s standards. Not to mention that aircraft of the pioneering days proved tricky to handle and the likelihood that it flew without someone at the controls while landing without incident may be deemed implausible.

Now John Brown, historian and author of gustave-white.com, argues that “These days, people don’t rely on editors or historians. If they want to know what happened in 1901, they simply read 1901 newspapers online.” I would agree with Brown that the internet provides a plethora of information in which people can conduct their own research. However, unless that individual is trained in cross examining evidence with other primary sources, then they are just as apt to be misdirected by the newspaper articles about Whitehead as the historians who claim that he flew; especially if you are unfamiliar with the history of newspapers. It is not unknown that some newspaper publications are known to stretch the truth or even write fantastical stories that have no semblance of truth, i.e. The National Enquirer or Weekly World News. However, these techniques had long been invented before modern practices. In fact, hoax journalism has been around since the first publishing of newspapers, but it would reach its apex in the 19th and early 20th century. In fact the famous author, Mark Twain, began his career with hoax journalism. With this in mind, many stories dating from this era cannot be taken at face value without some other evidence to support it. This is not to say that Whitehead’s airplanes were never built. In fact, there are many photographs with Whitehead posing in front of his invention; however, none show the aircraft in flight. Many of Whitehead’s supporters claim that news of his flight quickly spread in the U.S. and Europe. While this is true, it is interesting to note that while the story was printed in over eighty papers, including the Boston Transcript and the New York Herald, it was not published in the other four daily newspapers in Bridgeport where the flight took place. In fact, the story did not even make the front page of The Bridgeport Herald, but rather it was found in the “Features” section.

Let’s take the theory of hoax journalism out of the equation and focus on Whitehead’s explanation of his flight. In the June 1901 issue of Scientific American, he stated that the Number 21 could turn in the air by varying speed of the propellers. It is described as the engine pumping gas under high pressure to pistons driving the propellers in which he could vary the pressure of the gas to each prop. In the story published in The Bridgeport Herald, the engine is described as being fueled by “rapid gas explosions” from acetylene generated from calcium carbide. So this gives us a better description of Whitehead’s design. However, in the same article he stated, “I had no means of steering by using the machinery” and that “he simply shifted his weight more to one side than the other”.

Now let us assume that the newspaper article(s) had misspoke about the accounts of how Whitehead’s experiments took place. Let’s look at the evidence that remains. Unfortunately, as mentioned before, there are no photographs proving the aircraft in flight. There is a lithograph provided by supporters of Whitehead’s claim, but any drawing can be created by from a talented artist (see insert). Also, Whitehead was not able to duplicate his achievements. After completing three successful flights with powered aircraft, Whitehead then goes on to build more gliders. If he had positive results, wouldn’t an inventor continue with perfecting his design? Not to mention there is evidence that in 1906 and 1908 Whitehead built two aircraft for Stanley Beach, son of the editor of Scientific American, in which both designs failed. Supporters argue that Whitehead had more of a mechanic and did not have a propensity for bookkeeping. Still, it begs the question, why could he not reproduce his earlier results?

The last argument that I will delve into is the replicas that have been built by contemporary designers. According to the supporters, in the 1980s and 1990s, several replica-versions of Number 21 were flown in the U.S. and Germany thus proving that those built by Whitehead were capable of flying “and most likely did”. The opposition researched this concept of “new archaeology” which refers to the discipline of recreating “the circumstances of an historic or prehistoric event as closely as possible” while keeping in mind the issues that come up “using the technology available at the time” in order “to better understand that event and the people who lived through it” (wright-brothers.org). The purpose of these experiments is to test the possibility of it working, not to prove that it indeed occurred. With this information, the flights conducted with the Whitehead replicas do not prove that he ever flew although supporters use this as part of their argument that he did. Either way, the replicas used modern ultralight engines and high-speed propellers which ultimately defeats the purpose of the experiment as this technology did not exist in Whitehead’s time.

This debate has been discussed for the better part of a century. Some Whitehead supporters often mention the unusual agreement on behalf of the Smithsonian and the Wright brothers estate as one of the major reasons why Whitehead is not credited as being first in flight. The agreement reads as follows:

Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities administered for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright Airplane of 1903, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight.

This may seem absurd that the Smithsonian Institute was forced to agree to such terms, but the history is more complex. While today it is widely accepted that the Wright brothers were first in flight, this was not the case in the early 20th century. The Wright brothers fought to protect their patents while other builders quickly tried to find ways around them. One famous dispute occurred between the Wrights and Glenn Curtiss and the consequential “Patent Wars”. To provide the backstory of the agreement, Curtiss rebuilt an experimental aircraft designed by Samuel Langley on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution in order to prove that other aircraft could have flown before the Wright’s Flyer in 1903. This resulted in a divide between the Wright brothers and the Smithsonian Institute and would not be resolved until 1948 when the aforementioned agreement was made. It was only at this time that the Wright Flyer was returned from Europe to the Smithsonian museum to be put on display.

As for my research, much of it came from the primary sources of newspapers articles and publications from Whitehead’s era. I also pulled from previous researcher’s findings and relied on much from the two main web sources that represent both sides of the debate: gustavewhitehead.org, gustave-whitehead.com, and wright-brothers.org. While the websites were biased in their opinions, I used other resources to either contradict or support their findings. So did Gustave Whitehead achieve flight before the Wright brothers? With the evidence at hand, it does not seem plausible. However, if new evidence comes up to dispute the Wright brothers’ claim then I am certain historians will adjust the canons of history. Meanwhile, there is not enough to overturn the Wright brothers’ place in aviation history as first in flight.

I thought it to be exciting that this topic has sparked historians and aviation-buffs to re-examine the evidence to possibly find a new truth of who was first in flight. John Brown, historian and web manager for gustave-whitehead.com argues, “These days, people don’t rely on editors or historians. If they want to know what happened in 1901, they simply read 1901 newspapers online.” I would agree with Brown that the internet provides a plethora of information in which people can conduct their own research. However, unless that individual is trained in cross examining evidence with other primary sources, then the are just as apt to be misdirected by the newspaper articles about Whitehead as the historians who claim that he flew. I am reminded of a favorite historian, Keith Jenkins, who argues the concept that the real truth of the past is unattainable. In other words, someone might think they are learning the facts of what happened during a point in history, such as the Wright brothers being first in flight, but in reality the reader is absorbing the historian’s perception of the facts and thus the author’s relation to the truth. Two historians may look at the same facts, but their training and experiences that they have may heavily influence the narrative that the historian writes. Consequently, the reader is left to wonder whose “truth” is correct. Jenkins does not believe this situation to be defective. He stresses that each different reading can add to the general understanding of the past as a whole. Jenkins states that “to be in control of your own discourse means that you have the power over what you want history to be rather than accepting what others say it is”. This view is liberating for the field of history and its scholars, for it allows an historian to deconstruct the history of another and thus incorporate their interpretations in the overall discussion of the topic at hand. So what does this mean for you? You have the power to question historical writing of your predecessors and while the truth will never be ultimately found, each historical narrative will add to the canons of history and thus continuing the quest of better understanding the past.

For further reading:

Case for Gustave Whitehead – wright-brothers.org

Collection of Several Primary Sources including Bridgeport Herald Article

Gustave Whitehead: Did He Beat the Wright Brothers into the Sky?

Gustave Whitehead’s Flying Machines (gustavewhitehead.org)

Initially I had planned to post something on the hot topic of Boeing and its unfortunate luck with the new 787 Dreamliner. However, through the course of my research, I came across an interesting historical video. One thing about research is that if you keep an open mind, you never know what you might find. Usually I write a note to remind myself to come back to it, but this time I just couldn’t resist. So I’ve pushed Boeing to the side for now and decided to share this little treasure with you. Besides, I don’t think Boeing’s problem is going to be solved between now and when I do decide to write about it.

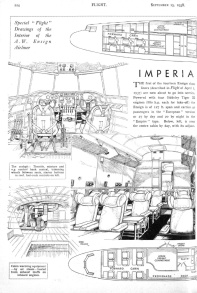

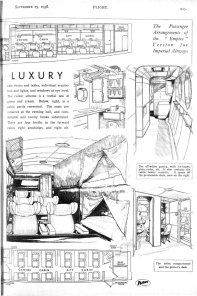

Now you’re probably wondering, what happened on this day in aviation history? January 24, 1938 marks the first flight of the Armstrong-Whitworth A.W. 27 “Ensign”. Designed for the British airliner, Imperial Airways (later bought by British Airways), it was the largest passenger land aircraft of its time. The AW27 was a high-wing cantilever monoplane of light alloy construction. Its design consisted of a semi-monocoque fuselage and retractable landing gear with a castoring tail wheel. Its interior was divided into separate cabins; one model possessed four cabins that seated forty passengers while the other had three cabins that accommodated twenty-seven passengers on day trips or twenty passengers with sleeping arrangements for overnight travel. Only fourteen AW27s were built to which Imperial Airways flew throughout Europe and Asia. With the onset of WWII, the Royal Air Force retrofitted the airplane into the fleet for the use of ferrying RAF personnel. The final flight of the AW27 was a passenger flight from Cairo to Hurn (Dorset, England) in June 1946. No surviving AW27s exist today.

The video below includes a series of press releases from Imperial Airways boasting their new passenger aircraft’s size, luxury, and grandeur. Take note of the tire size in comparison to the people standing next to them. For its time, it was quite an impressive airplane.

Specs

Crew: 5 (captain, first officer, radio operator, 2 cabin stewards)

Capacity: European Routes – 40 passengers; Asian Routes – 27 passengers

Wingspan: 123 feet

Length: 114 feet

Height: 23 feet

Empty Weight: 35,075 lbs.

Loaded Weight: 55,500 lbs.

Powerplant: 4 x Wright GR-1820-G102A geared radial engines; 1,100 hp each

Number Built: 14

Performance

Max Speed: 210 mph

Cruise Speed: 180 mph

Range: 1,370 miles @ 5,000 feet

Service Ceiling: 24,000 feet when fully loaded

Rate of Climb: 900 feet/minute

I had the pleasure of meeting Colonel Bud Anderson last year at an awards banquet held by the Northern California Aero Club. As the honored guest, he told the audience about his experiences during WWII flying his P-51 Mustang. He served two combat tours, flying 116 combat missions (480 hours) and destroyed 16 1/4 enemy aircraft in aerial combat and one on the ground. To explain the 1/4 kill, Col. Anderson shared the victory with other members of his squadron. As he explains the event:

“We were engaged in a wild dogfight with some ME109’s and ended up on the deck. During the engagement I noticed a large shadow moving on the ground. After we finished off the ME109’s I gathered my flight of four together and investigated the mysterious shadow. It turned out to be a camouflaged HE111 trying to get out of the area by flying right on the deck. We pulled up along side and set up a regular gunnery training pattern each taking a turn. All flight members got in one or two passes. We silenced the rear gunner, set one engine on fire and the other smoking badly. The pilot made a belly landing in an open field but the HE111 broke in half and caught fire. We saw at least two crew members escape. Everyone in my flight of four P-51’s had made a firing pass on the bomber so I shared the victory with all flight members.”

When asked what is his favorite aircraft, his loyalty remains with the P-51D, especially his “Old Crow” which he named after a whiskey he preferred. He jokes that he tells his Baptist friends that it is named after the smartest bird that flies in the sky, but in actuality his plane is named after the Kentucky straight bourbon whiskey of the same name. A good name for a great plane. It is arguably the plane that won the war. Originally ordered by the British in 1939, the Mustang would go on to be the primary fighter aircraft to dominate the skies. It’s ability to carry 450 gallons of fuel, the aircraft had a range of 2000 miles making it perfect to escort the bombers for the duration of long-range missions.

Before the U.S. entered the war, it produced various supplies for the Allied forces. The British Purchasing Agency originally purchased all the P-40’s that Curtiss-Wright Corporation could build. The British knowing they needed more planes approached North American Aviation to build additional P-40’s but the company did not favor the idea of constructing a competitor’s product. Instead they produced a new fighter that used the same American-built Allison engine V-1710-39, the P-51. Originally named the Apache, it was later named the Mustang after the wild North American horses.

Once the U.S. entered the war, the Mustang remained the main fighter plane combating the German Luftwaffe. Col. Anderson’s model, the P-51D, was the most produced at 9600 aircraft. It’s combat record includes 4950 air kills, 4131 ground kills, 230 V-1 kills. Only 300 P-51s exist today with about only half flying. Bud Anderson has his “Old Crow” which you can learn more about in his book, To Fly and Fight: Memoirs of a Triple Ace. I recommend his book for a pilot’s perspective on WWII. His straightforward narrative reads as if he is in a conversation with his reader. Rather than listing combat maneuvers and mission logs, he provides an in-depth description of the emotions and logistics of his experiences in combat. Intermixed with a little humor and stories of his personal life, the book is an exciting read. An accomplished pilot, Col. Anderson has flown over 130 aircraft, logging 7500 flight hours. His 30 year military career included: Commander of an F86 Squadron in post war Korea; Commander of an F-105 Wing on Okinawa; served in Southeast Asia as Commander of 355th Tactical Fighter Wing; assignment to the Pentagon as an advanced R&D staff planner and as Director of Operational Requirements. He has been decorated 25 times to include 2 Legion of Merits, 5 Distinguished Flying Crosses, the Bronze Star, 16 Air Medals, the French Legion of Honor and the French Croix de Guerre, in addition to multiple campaign and service ribbons. A true American hero.

Refer to Bud Anderson’s webpage for more information, excerpts from his book, and videos narrating his experiences in the war: http://www.cebudanderson.com/

This airplane is often forgotten when discussing WWII aircraft. For almost two decades this plane was lost to history after the last flying model crashed in the 1970s. A loose fuel cap caused the plane to catch fire forcing the pilot and passenger to evacuate. Airplane enthusiasts Doug Champin and Herb Tischler lead a team to rebuild the F3F in the late 1980s. They successfully restored four F3F models over the period of four years. Until recently, they were the only F3’s in operable condition. Sonoma Vintage Aircraft Company in California possesses the fifth after a successful first flight this past September (see video insert below).

(On a personal note, the pilot of this plane was my pilot who took me up for my first aerobatic flight in a 1942 Stearman. My flight was later that same day that this F3F flew for the first time.)

The F3F happened to be the last American biplane fighter delivered to the Navy. This biplane never saw combat during WWII, but it did prove useful as a trainer to military pilots. It first entered into service in 1936 with the order of 54 planes. A modernized version of the biplane, the craft included an enclosed cockpit and retractable landing gear. The landing gear is a manual operation and is known to be somewhat cumbersome when operating. As a tailwheel, the pilot will typically fly with the left hand on the throttle and right hand on the stick. With the Grumman F3F, the pilot must use their right hand to crank the landing gear either in the up or down position; thus using their left hand to fly the plane. It take 26 turns before the landing gear is fully in place which can make the taking off procedures rather hectic!

In 1937, the Navy purchased 81 F3F-2 to equip two Marine Corps fighting squadrons and the USS Enterprise (CV-6). The second

model of the F3F possessed minor improvements over its predecessor. Grumman had corrected the stability problems found on the F3F-1 by extending the fuselage 22 inches from 21’5″ to 23’2″ and expanding the wing area to 260 from 230 square feet.

The Navy’s last order of the F3F-3 in 1938 and ’39 served with the Fighting Squadron Five on the USS Yorktown (CV-5). This aircraft included the following modifications: Pratt & Whitney engine replaced the Wright R-22 “Cyclone” and had 950 hp; 2-bladed prop traded for the Hamilton-Standard 3-bladed assembly; and increase rudder area to counter increased engine torque. The improvements to the F3F-3 advanced the performance of the plane: increased speed of 264 from 231 mph; climb rate from 2050 to 2750 feet per minute; and the service ceiling rose from 27,000 to 33,200 feet.

After replaced with the F4F Wildcat in 1941, the F3F would be used as advanced trainers mainly operated by Pan American Airways. A side note: Pan Am halted their commercial flights and prioritized their efforts to training the majority of ferry pilots during the war. The last F3F to serve our military forces retired in November 1943.

A great video that coincides with this post:

Specs

Role: Fighter Aircraft Manufacturer: Grumman Designer: Leroy Grumman

Propulsion

- Single-engine 1 x Wright R-1820-22 “Cyclone” 9-cylinder radial engine; 950 hp

Performance

Max Speed: 264 m/h

Max Cruising Speed: 150 m/h

Initial Rate of Climb: 2800 ft/m

Service Ceiling: 33,200 ft.

Max Range (no reserves) 850 nm

Weight (empty) 3285 lbs.

Max Takeoff 4795 lbs.

Dimensions

Wing Span: 32’0”

Length: 23’2”

Height: 9’4”

Wing Area: 260 sq.ft

Seating Capacity 1

Armament

Guns:

- 1 x 0.30 in. (7.62 mm) M1919 machine gun, 500 rounds (left)

- 1x 0.50 in (12.7 mm) M2 machine gun, 200 rounds (right)

Bombs:

- 2 x 116 lb. (52.6 kg) MK IV bombs, one under each wing

San Francisco celebrated its annual Fleet Week with the arrival of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard this past weekend. It is a time honored tradition beginning in 1935 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt thought it necessary to reinstate our Naval presence on a global scale. At the time tensions started to heighten in Europe with the onset of WWII and FDR prepared necessary precautions, such as strengthening our armed forces. To rally American citizens for military support, FDR organized military personnel to be present at the 1935 California Pacific International Exposition in San Diego. The initial purpose of the event centered around exhibits on history, arts, science and industry, but it would evolve into what it is today: the celebration of our Sailors, Marines, and Coastguardsmen. The event is open to the public allowing civilians to meet with military service members, tour their ships, and become familiar with our nation’s defense. Fleet Week organizers’ goal is to “foster awareness of the contributions made by enlisted military personnel and their families; to enhance relationships between civilian, business and military communities; to provide events that military personnel and their families can attend at little or no cost; and to raise funds for charitable efforts benefitting enlisted service members and their families.” Quoted from San Diego’s Fleet Week press release, it resonates with the other hosting cities’ aspirations. Now I have a slight bias towards all of this. I am a proud wife a United States Sailor and I think this type of event is beneficial to our society. It enhances the relationship between the citizens and their nation’s defense. I find it helps our society better understand our military while promoting respect for those who serve and their families.

So how does this all fit in with my blog about aviation? While touring through San Francisco this weekend I realized that the city possesses a critical milestone in Naval Aviation history. On January 18, 1911 the first aircraft successfully departed and landed on a ship on the San Francisco Bay. To accomplish this feat, modifications were made to the Pacific Fleet’s armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania by Glenn Hammond Curtiss. Known as the “Father of Naval Aviation,” Curtiss forever changed the structure of the American Navy with his innovative designs for naval aircraft. He began with the aircraft carrier design by retrofitting the Pennsylvania with a 120 by 30 foot platform. The platform included a series of ropes with sandbags attached to the ends to which the hooks on the airplane’s landing gear would catch and bring to a rapid halt. The Pennsylvania’s crew rigged a canvas along the perimeter of the deck in case of overrun or if the airplane swerved towards the edge of the ship. Fortunately, no such emergency occurred and pilot Eugene Ely flew the Curtiss pusher biplane both on and off the platform. Initially, the Navy saw no benefit from the aircraft carrier design and decided to forgo its construction (the British Royal Navy would take the lead in its development). However, the U.S. Navy asked Curtiss to build a seaplane that could be transported on the deck of a battleship. On January 26, 1911 Curtiss successfully demonstrated the first practical seaplane in San Diego Harbor. The plane landed next to the battleship on the water and then raised onto the deck of the ship. Thus marked the beginning of naval aviation in America.