For the month of April, I decided to do something a little different. I left it to my readers to ask the questions to discover more about something that they did not know. I was happy to see a few inquiries come back. The last week of this month will focus on the answers to your questions. Thank you to all who participated and for those who did not get their request in, please email me at loveofflight@thepublichistorian.net or post a message on this webpage and I will get started on the research for you.

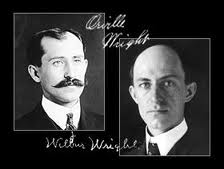

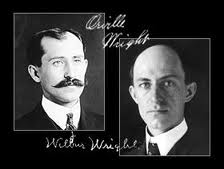

One of the first inquiries I received was in regards to the Whitehead-Wright controversy of who was really first in flight. This debate has been sparked every so often in the media questioning who should take the fame for achieving man’s ability to fly heavier-than-air machinery. Let’s first introduce the characters in our historical narrative. Many of us aviation buffs are familiar with the Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur, who flew their flyer above the outer banks of North Carolina in 1903. Known as the individuals to be “first in flight” they laid the foundation for the aviation industry.

One of the first inquiries I received was in regards to the Whitehead-Wright controversy of who was really first in flight. This debate has been sparked every so often in the media questioning who should take the fame for achieving man’s ability to fly heavier-than-air machinery. Let’s first introduce the characters in our historical narrative. Many of us aviation buffs are familiar with the Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur, who flew their flyer above the outer banks of North Carolina in 1903. Known as the individuals to be “first in flight” they laid the foundation for the aviation industry.

Gustave Whitehead (1874-1927)

Little did anyone know that there was another inventor that claimed that title a few years prior. Gustave Whitehead, an immigrant from Bavaria, Germany who was born on January 1, 1874. Whitehead had always been fascinated with flight. Schoolmates dubbed him “The Flyer” due to his intense study of birds and building model parachutes and gliders. He pursued his passion for aviation and in 1895 decided to immigrate to America to continue his research.

According to the historians of gustavewhitehead.org, the “story of Gustave would not be known today if it wasn’t for dedicated researchers from 1937 on who have been tracking down evidence to substantiate the Whitehead first flight claim. In particular, journalist Stella Randolph who wrote ‘The Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead’ (1935 publication of Popular Aviation) and ‘Before the Wright flew: The story of Gustave Whitehead’” (1937). According to Randolph and her co-writer, Harvey Phillips, Whitehead successfully flew three different powered aircraft. His first flight conducted in 1899, Whitehead flew in a steam-driven aircraft. Then in August of 1901, he made another flight with a gas-powered aircraft, designated “Number 21” and with “Number 22” the following year. If true, these flights would prove that Whitehead preceded the Wright brothers in powered flight. (to see article, click here)

Gustave Whitehead with Number 21

courtesy of unmuseum.org

Several of Randolf and Phillips’ assertions in the article are a bit peculiar and have drawn critics to question the validity of their evidence. Let’s put to the side that it was more than three decades after the flights and nine years after Whitehead’s death in which the article was written, which could possibly taint any evidence that existed, i.e. people’s memory of the event and that no follow up could be made with Whitehead. Much of the article drew from a previous story by The Bridgeport Herald newspaper published on August 18, 1901. The journalist claimed he witnessed a night test of the plane in which at first it was unpiloted but filled with sand bags with a second follow-up flight with Whitehead at the controls. To begin, an initial testing of an aircraft’s flight ability at night is extremely dangerous even by today’s standards. Not to mention that aircraft of the pioneering days proved tricky to handle and the likelihood that it flew without someone at the controls while landing without incident may be deemed implausible.

Now John Brown, historian and author of gustave-white.com, argues that “These days, people don’t rely on editors or historians. If they want to know what happened in 1901, they simply read 1901 newspapers online.” I would agree with Brown that the internet provides a plethora of information in which people can conduct their own research. However, unless that individual is trained in cross examining evidence with other primary sources, then they are just as apt to be misdirected by the newspaper articles about Whitehead as the historians who claim that he flew; especially if you are unfamiliar with the history of newspapers. It is not unknown that some newspaper publications are known to stretch the truth or even write fantastical stories that have no semblance of truth, i.e. The National Enquirer or Weekly World News. However, these techniques had long been invented before modern practices. In fact, hoax journalism has been around since the first publishing of newspapers, but it would reach its apex in the 19th and early 20th century. In fact the famous author, Mark Twain, began his career with hoax journalism. With this in mind, many stories dating from this era cannot be taken at face value without some other evidence to support it. This is not to say that Whitehead’s airplanes were never built. In fact, there are many photographs with Whitehead posing in front of his invention; however, none show the aircraft in flight. Many of Whitehead’s supporters claim that news of his flight quickly spread in the U.S. and Europe. While this is true, it is interesting to note that while the story was printed in over eighty papers, including the Boston Transcript and the New York Herald, it was not published in the other four daily newspapers in Bridgeport where the flight took place. In fact, the story did not even make the front page of The Bridgeport Herald, but rather it was found in the “Features” section.

Let’s take the theory of hoax journalism out of the equation and focus on Whitehead’s explanation of his flight. In the June 1901 issue of Scientific American, he stated that the Number 21 could turn in the air by varying speed of the propellers. It is described as the engine pumping gas under high pressure to pistons driving the propellers in which he could vary the pressure of the gas to each prop. In the story published in The Bridgeport Herald, the engine is described as being fueled by “rapid gas explosions” from acetylene generated from calcium carbide. So this gives us a better description of Whitehead’s design. However, in the same article he stated, “I had no means of steering by using the machinery” and that “he simply shifted his weight more to one side than the other”.

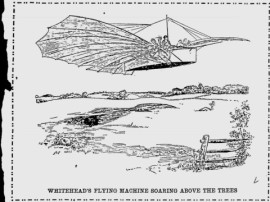

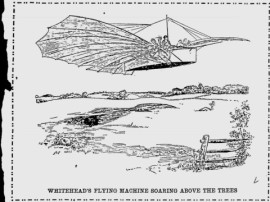

Gustave Whitehead flying machine drawing courtesy of gustave-whitehead.com

Now let us assume that the newspaper article(s) had misspoke about the accounts of how Whitehead’s experiments took place. Let’s look at the evidence that remains. Unfortunately, as mentioned before, there are no photographs proving the aircraft in flight. There is a lithograph provided by supporters of Whitehead’s claim, but any drawing can be created by from a talented artist (see insert). Also, Whitehead was not able to duplicate his achievements. After completing three successful flights with powered aircraft, Whitehead then goes on to build more gliders. If he had positive results, wouldn’t an inventor continue with perfecting his design? Not to mention there is evidence that in 1906 and 1908 Whitehead built two aircraft for Stanley Beach, son of the editor of Scientific American, in which both designs failed. Supporters argue that Whitehead had more of a mechanic and did not have a propensity for bookkeeping. Still, it begs the question, why could he not reproduce his earlier results?

The last argument that I will delve into is the replicas that have been built by contemporary designers. According to the supporters, in the 1980s and 1990s, several replica-versions of Number 21 were flown in the U.S. and Germany thus proving that those built by Whitehead were capable of flying “and most likely did”. The opposition researched this concept of “new archaeology” which refers to the discipline of recreating “the circumstances of an historic or prehistoric event as closely as possible” while keeping in mind the issues that come up “using the technology available at the time” in order “to better understand that event and the people who lived through it” (wright-brothers.org). The purpose of these experiments is to test the possibility of it working, not to prove that it indeed occurred. With this information, the flights conducted with the Whitehead replicas do not prove that he ever flew although supporters use this as part of their argument that he did. Either way, the replicas used modern ultralight engines and high-speed propellers which ultimately defeats the purpose of the experiment as this technology did not exist in Whitehead’s time.

This debate has been discussed for the better part of a century. Some Whitehead supporters often mention the unusual agreement on behalf of the Smithsonian and the Wright brothers estate as one of the major reasons why Whitehead is not credited as being first in flight. The agreement reads as follows:

Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities administered for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright Airplane of 1903, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight.

This may seem absurd that the Smithsonian Institute was forced to agree to such terms, but the history is more complex. While today it is widely accepted that the Wright brothers were first in flight, this was not the case in the early 20th century. The Wright brothers fought to protect their patents while other builders quickly tried to find ways around them. One famous dispute occurred between the Wrights and Glenn Curtiss and the consequential “Patent Wars”. To provide the backstory of the agreement, Curtiss rebuilt an experimental aircraft designed by Samuel Langley on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution in order to prove that other aircraft could have flown before the Wright’s Flyer in 1903. This resulted in a divide between the Wright brothers and the Smithsonian Institute and would not be resolved until 1948 when the aforementioned agreement was made. It was only at this time that the Wright Flyer was returned from Europe to the Smithsonian museum to be put on display.

As for my research, much of it came from the primary sources of newspapers articles and publications from Whitehead’s era. I also pulled from previous researcher’s findings and relied on much from the two main web sources that represent both sides of the debate: gustavewhitehead.org, gustave-whitehead.com, and wright-brothers.org. While the websites were biased in their opinions, I used other resources to either contradict or support their findings. So did Gustave Whitehead achieve flight before the Wright brothers? With the evidence at hand, it does not seem plausible. However, if new evidence comes up to dispute the Wright brothers’ claim then I am certain historians will adjust the canons of history. Meanwhile, there is not enough to overturn the Wright brothers’ place in aviation history as first in flight.

I thought it to be exciting that this topic has sparked historians and aviation-buffs to re-examine the evidence to possibly find a new truth of who was first in flight. John Brown, historian and web manager for gustave-whitehead.com argues, “These days, people don’t rely on editors or historians. If they want to know what happened in 1901, they simply read 1901 newspapers online.” I would agree with Brown that the internet provides a plethora of information in which people can conduct their own research. However, unless that individual is trained in cross examining evidence with other primary sources, then the are just as apt to be misdirected by the newspaper articles about Whitehead as the historians who claim that he flew. I am reminded of a favorite historian, Keith Jenkins, who argues the concept that the real truth of the past is unattainable. In other words, someone might think they are learning the facts of what happened during a point in history, such as the Wright brothers being first in flight, but in reality the reader is absorbing the historian’s perception of the facts and thus the author’s relation to the truth. Two historians may look at the same facts, but their training and experiences that they have may heavily influence the narrative that the historian writes. Consequently, the reader is left to wonder whose “truth” is correct. Jenkins does not believe this situation to be defective. He stresses that each different reading can add to the general understanding of the past as a whole. Jenkins states that “to be in control of your own discourse means that you have the power over what you want history to be rather than accepting what others say it is”. This view is liberating for the field of history and its scholars, for it allows an historian to deconstruct the history of another and thus incorporate their interpretations in the overall discussion of the topic at hand. So what does this mean for you? You have the power to question historical writing of your predecessors and while the truth will never be ultimately found, each historical narrative will add to the canons of history and thus continuing the quest of better understanding the past.

For further reading:

Case for Gustave Whitehead – wright-brothers.org

Collection of Several Primary Sources including Bridgeport Herald Article

Gustave Whitehead: Did He Beat the Wright Brothers into the Sky?

Gustave Whitehead’s Flying Machines (gustavewhitehead.org)

Gustave Whitehead – Pioneer Aviator (gustave-whitehead.com)

Hoax Journalism

Keith Jenkins – Rethinking History

One of my resolutions this year is to be more digilent in my posts on this website. My apologies dear readers for my extended absence. But enough about that, let’s celebrate the new year!

One of my resolutions this year is to be more digilent in my posts on this website. My apologies dear readers for my extended absence. But enough about that, let’s celebrate the new year!